CeCl3-Promoted Simultaneous Photocatalytic Cleavage and Amination of Cα–Cβ Bond in Lignin Model Compounds and Native Lignin

It remains challenging to achieve valuable platform chemicals from lignin because of its complicated polymeric structure and inherent inert chemical activities. So far, only a few examples have been reported for the selective cleavage of C–C bonds in lignin due to their intrinsic inertness and ubiquity. Here, we present a simple and commercially available cerium(III) chloride (CeCl3)-promoted photocatalytic depolymerization strategy to realize the simultaneous cleavage and amination of Cα–Cβ bond in a variety of lignin model compounds at room temperature. This procedure does not require any pretreatments and breakdown of C–O bonds or loss of γ-CH2OH group to generate aldehydes (up to 97%) and N-containing products (up to 95%) in good to excellent yields. Additionally, this CeCl3-based photocatalyst system could maintain excellent catalytic performance even after 10 sequential cycles with new starting materials. Moreover, this approach realizes the precise control over the reaction via switching the external light stimuli on/off. Further, this method is effective for the depolymerization of real lignin, thus affording the corresponding cleavage and amination products of Cα–Cβ bonds.

Introduction

The increasing global demand for energy and fuels has urged us to explore a sustainable alternative to the depleted fossil resources. The production of valuable aromatic compounds from the depolymerization of lignin, the second most abundant non-edible biomass resource other than cellulose and the most abundant aromatic resources on earth,1 have attracted intense attention in recent years. However, only less than 2% of lignin is utilized to deliver commercial products2 due to its composition of a variety of distinct and chemically different bonding motifs,1–4 with each demanding different reaction conditions for selective depolymerization. Various significant advancements have been made with C–O bond cleavage in both lignin model compounds and native lignin.5–14 In sharp contrast, it remains a major challenge to achieve the selective cleavage of the C–C bond due to their intrinsic inertness and ubiquity.15 Some progress has been achieved in the selective cleavage of C–C bond in lignin model compounds with the catalysis of transition metal–based complexes (M = Cu, V, Fe, Ru, Ir, Rh)16–25 or the highly efficient, photoredox catalyst systems.17,25,26 More recently, Knowles and co-workers27 demonstrated that the photoredox catalysis could enable the β-scission of both tertiary alcohols and cyclic aliphatic alcohols, as well as the lignin model compounds at room temperature (RT). Our group also disclosed that iridium (Ir) complex could achieve the redox-neutral, photocatalytic cleavage of C–C bond in a wide range of lignin models, as well as the native lignin at RT.28 However, the use of the noble metal–based catalyst would certainly, increase the production cost. Therefore, it is more desirable to develop a low-cost photocatalyst system, which would possess good stability and high efficiency for the practical application of lignin depolymerization. On the other hand, to maximize the lignin valorization, it is of crucial importance to produce high value-added platform chemicals from lignin depolymerization.

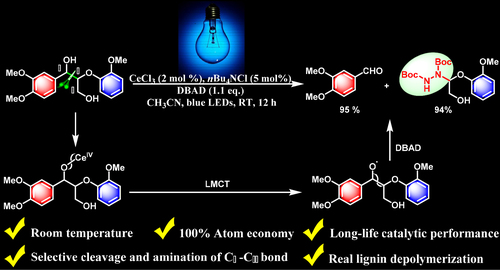

Cerium is the most abundant rare earth element, and cerium (III) compounds exhibit widespread application in solid luminescent materials and organic synthesis.29–31 As an inexpensive, commercially available Lewis acid, cerium(III) trichloride (CeCl3) also demonstrates a vital role in photoredox catalysis.32–36 Most recently, Zuo et al32 successfully employed cerium salts to realize the photocatalytically selective C–H amination of methane through the catalysis of alkoxy radicals generated from simple alcohols.34 They discovered that CeCl3 could also be applied to the photocatalytic ring opening of cycloalkanols. These excellent examples indicated that the presence of a hydroxyl (OH) group is critical for such reactions. It is well-known that the benzylic alpha hydroxyl groups (α–OH) are abundant in lignin as β-O-4 structures featuring a secondary benzylic hydroxyl group at the Cα position and a primary hydroxyl group at Cγ position, accounting for ∼ 50% of all lignin linkages.37 Therefore, we envisioned that CeCl3 could promote the cleavage of Cα–Cβ bonds in lignin; additionally, because cerium is readily abundant in nature, it would make CeCl3 an ideal catalyst for lignin depolymerization, as it would cut the product cost substantially. Herein, we demonstrate a CeCl3-promoted, one-pot, visible light–driven photocatalytic strategy to not only achieve the selective cleavage of Cα–Cβ bonds in a wide-range of lignin model compounds such as β-O-4 and β-1 models but also furnish aldehyde (up to 97%) and N-containing products (up to 95%) through the amination of Cα–Cβ bond (Scheme 1) at RT, without any pretreatments and breakdown of C–O bonds or loss of γ-CH2OH group. More importantly, this method is efficient for natural lignin depolymerization and affords the corresponding functionalized products. To our best knowledge, our current study is the first example of simultaneous cleavage and amination of C–C bonds in both lignin model compounds and native lignin, and thus, it provides an economic-viable way for the synthesis of useful N-containing complexes.

Scheme 1 | Visible light–driven CeCl3-photocatalyzed selective cleavage and amination of Cα–Cβ bond in β-O-4 lignin model compound.

Methods

Materials and general procedures

All chemical syntheses and air- and moisture-sensitive materials manipulations were carried out in inflamed Schlenk-type glassware on a dual-manifold Schlenk line or a high-vacuum line or an argon-filled glovebox. Phenol; 2-methoxyphenol; diisopropylamine; 2-bromoacetophenone; 2-bromo-4′-methoxyacetophenone; 2-bromo-3′-methoxyacetophenone; sodium borohydride; ethyl (2-methoxyphenoxy)acetate; benzylmagnesium chloride; 2-bromo-4'-hydroxyacetophenone; formaldehyde; inorganic salts; solvents; and the standard substances benzaldehyde, 4-methoxybenzaldehyde, 3,4-dimethoxybenzaldehyde, 3,4,5-trimethoxybenzaldehyde were purchased from Adamas-beta®, Shanghai, China. n-BuLi (1.6 M solution in hexanes), guaiacol, CeCl3, nBu4NCl, nBu4NI, nBu4PCl, nBu4NOAc, and di-tert-butyl azodicarboxylate (DBAD) were purchased from J&K (Beijing, China). All chemicals obtained were used as received unless otherwise specified. Namely, tetrahydrofuran (THF) was dried over sodium/potassium alloy and distilled under a nitrogen atmosphere before use for the synthesis of the lignin model compounds. Acetonitrile (CH3CN) was dried over CaH2 distilled under a nitrogen atmosphere prior to use for light-induced catalytic reactions.

Each reaction was monitored by thin-layer chromatography (TLC), visualizing with ultraviolet (UV) light. Column chromatography purifications were performed using silica gel. The reaction mixtures were analyzed using Alliance High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) system (Waters, Milford, MA), equipped with autosampler, C18 column (length: 75 mm, internal diameter: 4.6 mm, temperature: 35 °C), and UV/vis detector (λ = 220 nm). A mixture of methanol/water (CH3OH∶H2O; 40∶60) was used as the mobile phase, with a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min. Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectra were recorded on an Avance II 500 (500 MHz, 1H; 126 MHz, 13C) instrument (Bruker, Shanghai, China) at RT. Chemical shifts for 1H and 13C spectra were referenced to internal solvent resonances. Mass spectra recordings were obtained using the Bruker MicroTOF Q II. Gas chromatography (GC) was analyzed using the Shimadzu GC-2014 (Beijing, China), and a flame ionization detector with the following parameters: carrier gas: N2 (2 mL/min); program temperature: 60 °C (1 min), 5 °C/min to 210 °C (7 min), and 5 °C/min to 220 °C (5 min); injector temperature: 250 °C; detector temperature: 250 °C; split ratio: 30; and injection volume: 5 μL. Yields were determined by GC analysis using naphthalene as an internal standard.

Light-induced catalytic reactions

A 10 mL Schlenk tube was charged with a lignin model compound (0.2 mmol, 1 eq.), CeCl3 (2 mol %), tetrabutylammonium chloride (nBu4NCl; 5 mol %), DBAD (1.1 eq), and 1.0 mL anhydrous acetonitrile (CH3CN) at N2 atmosphere. The reaction was irradiated with a 30 W blue LED lamp (λ = 460 nm) at RT for 12 h. The resulting mixture was dissolved to constant volume in a 50 mL volumetric flask and measured by HPLC.

Extraction and Depolymerization of Lignin

Extraction of lignin

We charged a round bottom flask with 10.0 g pine sawdust, 50 mL 1,4-dioxane, and 1.7 mL HCl (37 wt %), and heated to reflux at 85 °C in an oil bath for 3 h. After cooling to RT, the mixture was added with 3.36 g sodium bicarbonate (NaHCO3), stirred for another 30 min, after which it was filtered and washed with 10 mL of dioxane. Then the solution was concentrated at 40 °C under reduced pressure. The resulting dark-brown oil was diluted with 30 mL ethyl acetate (EtOAc) and added dropwise to 500 mL of hexane to precipitate the lignin. After filtration, the collected lignin was washed with hexane (50 mL), followed by diethyl ether (50 mL) for 5 min each while sonicating. The recovered lignin was dried overnight at RT in a desiccator to afford 1.01 g pine lignin.

Depolymerization of lignin

Under atmosphere N2 conditions, 50 mg of pine lignin, 4.9 mg of CeCl3, 4.9 mg nBu4NCl, and 50 mg DBAD were dissolved in 1.0 mL dry CH3CN, in a 10 mL Schlenk bottle. The reactor was illuminated under a Kessil H150B LED Grow Light (Richmond, CA, USA) at RT for 12 h. Then, still under nitrogen condition, the second batch of 4.9 mg of CeCl3 and 4.9 mg nBu4NCl was added, with subsequent illumination for another 12 h.

Results and Discussion

Optimization studies

In our initial studies, we observed the generation of aldehyde and hydrazinium products

through this photocatalytic depolymerization and functionalization of simple β-O-4

lignin model

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | Variation From the “Standard” Conditions (Entry 1) | Yield (%)b | |

|

|

|

||

| 1 | CeCl3 (2 mol %), nBu4NCl (5 mol %) | 95 | 94 |

| 2 | CeCl3 (0.5 mol %), nBu4NCl (1.5 mol %) | 89 | 90 |

| 3 | CeCl3 (2 mol %) | 43 | 40 |

| 4 | nBu4NI, instead of nBu4NCl | 0 | 0 |

| 5 | nBu4NOAc, instead of nBu4NCl | 0 | 0 |

| 6 | nBu4PCl, instead of nBu4NCl | 91 | 90 |

| 7 | No CeCl3 | 0 | 0 |

| 8 | No DBAD | 0 | 0 |

| 9 | No light | 0 | 0 |

| 10 | No light, 80 °C | 0 | 0 |

| 11c | Water (1.0 eq.) | 88 | 89 |

| 12c | Air atmosphere | 83 | 82 |

Scope of lignin models

It is recognized that there is a close correlation between the catalyst reactivity

and the lignin model substrate structure. With the optimized condition in hand, we

continued to investigate the efficacy of the CeCl3 catalyst system on the depolymerization of lignin model compounds with varying positions

of the methoxyl groups of the aromatic rings. Varying the methoxy group position on

either benzene ring (left, red) or the phenoxy group (right, blue) did not affect

the catalytic performance. The corresponding β-scission/amination product, aldehydes

(up to 96% yield) and hydraziniums (up to 95% yield) were produced in high to excellent

yields for the lignin model

Scheme 2 | Photocatalytic cleavage and amination of Cα–Cβ bond in β-1 lignin model compound P.

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | Substrate | Conv.(%)b | Yield (%)b | Entry | Substrate | Conv.(%)b | Yield (%)b | ||

| 1 |  |

95 |

|

|

9 |  |

92 | aa, 87 |

|

| 2 |  |

>99 |

|

|

10 |  |

>99 |

|

|

| 3 |  |

>99 |

|

|

11 |  |

>99 |

|

|

| 4 |  |

96 |

|

|

12 |  |

>99 |

|

|

| 5 |  |

98 |

|

|

13 |  |

96 |

|

|

| 6 |  |

99 |

|

|

14 |  |

>99 |

|

|

| 7 |  |

>99 |

|

|

15 |  |

>99 |

|

|

| 8 |  |

82 |

|

|

|||||

Collectively, these results suggest that this photocatalytic strategy is a simple

and convenient method that could not only achieve one-step, selective cleavage of

Cα–Cβ bond in lignin models at RT, but also furnish useful amination products. In particular,

such N-containing complexes could be transformed into valuable chemicals. For example,

product

Scheme 3 | Transformation of product bc into useful N-heterocyclic chemicals 1,3,4-oxadiazine and 1,2-diazetidine.

Mechanistic studies

In order to probe more insights into the CeCl3 catalytic reaction, several UV–vis experiments were conducted ( Supporting Information Figure S1). It turned out that lignin model

Figure 1 | (a) Reaction profiles for selective cleavage and amination of Cα–Cβ bond in β-O-4 lignin model A by CeCl3. (b) Time profile of photocatalytic cleavage and amination of Cα–Cβ bond in β-O-4 lignin model A by switching the light on/off.

Furthermore, the fact that the reaction was unfeasible in the dark suggested this photocatalytic cleavage and amination of Cα–Cβ bond in the lignin model substrate could be activated/deactivated by light, thus leading to the controlled regulation of the photocatalytic depolymerization process. To investigate the nature of this responsiveness, we performed the reaction by switching on/off of the external light stimuli. When the experiment was exposed to a 460 nm light source, an 18% conversion was achieved in 2 h (Figure 1b). After removal of the light source, no further conversion was notable during the time course of 1 h; however, reexposure to 460 nm light, led to further reaction progress. This cycle could be repeated several times to attain a quantitative conversion as high as ∼ 99%, indicating the exhibition of precise control of the photocatalytic Cα–Cβ bond scission/amination process.

Scheme 4 | Control experiments performed (a) by using (nBu4N)2CeIVCl6 instead of the mixture of CeCl3 and nBu4NCl; (b) with the addition of TEMPO; (c) by using compound A-CH3 with methoxy group as substrate instead of model A with an α-OH group.

Based on the above observations, we proposed a plausible mechanism for this photocatalytic

β-scission/amination of Cα–Cβ bond process (Figure 2), as follows: (1) In the presence of nBu4NCl, CeCl3 is coordinated to the lignin model

Figure 2 | The plausible reaction mechanism for CeCl3-promoted photocatalytic cleavage and amination of Cα–Cβ bond in lignin model A.

Practicability of the CeCl3-based photocatalytic system

A gram-scale reaction was performed by using lignin model

Figure 3 | Reuse experiment of the CeCl3-based photocatalytic system by using lignin model A as a substrate.

Degradation of trimeric lignin model and real lignin

The identification of such a highly efficient and selective photocatalytic system

for Cα–Cβ bond cleavage and amination at RT prompted us to apply this strategy to the depolymerization

of a more complex lignin model structure. A trimeric model compound (

Scheme 5 | Selective cleavage and amination of Cα–Cβ bonds in Trimer.

The success achieved in the depolymerization of lignin model compounds and the trimer inspired us to examine further the applicability of this CeCl3-based photocatalytic system on the depolymerization of real or natural product lignin. Through the extraction of pine sawdust with HCl/dioxane, we prepared the softwood pine lignin. After photocatalytic depolymerization, two-dimensional (2D) heteronuclear single-quantum coherence (HSQC) spectra of the lignin obtained indicated that the major peaks attributable to β-O-4 units (A) and phenylcoumaran (β-5) units (B) in the pine lignin had almost disappeared completely, and new cross peaks became apparent, which were consistent with the expected cleavage products (Figure 4). More specifically, selective cleavage of Cα–Cβ bond led to the disappearance of Aα (δC 73, δH 5.0 ppm) and Aβ (δC 84, δH 4.2 ppm) in β-O-4, as well as the formation of corresponding aldehyde group Vα (δC 192, δH 9.9 ppm) attributed to vanillin product (V) and Hβ (δC 94, δH 5.9 ppm) attributed hydrazine product (H). Furthermore, the aromatic regions peaks obtained from NMR spectra of the depolymerized lignin (Figure 4c and d) indicated that the majority of the following G-type lignin (G) found in pine lignin [G2 (δC 110, δH 6.9 ppm), G5 (δC 115, δH 6.7 ppm), and G6 (δC 119, δH 6.8 ppm)] were converted to aromatic ring [V2 (δC 108, δH 7.4 ppm), V5 (δC 115, δH 7.3 ppm), and V6 (δC 125, δH 7.4 ppm)] attributable to unit V. The GC analysis of products confirmed that ∼11.94 wt% (note: The N-containing part of the product came from DBAD rather than lignin.) of small aromatic compounds (hydrazine converted from phenols) could be obtained after the depolymerization of pine-dioxane lignin by this CeCl3-based photocatalytic strategy (Scheme 6 and Supporting Information Scheme S2–S4, Figure S5). Altogether, these results demonstrated that this CeCl3-based photocatalytic strategy is an effective method for achieving the selective cleavage and amination of Cα–Cβ bond in natural lignin depolymerization.

Figure 4 | Two-dimensional HSQC spectra of pine lignin in d-DMSO. (a) and (c) are pine lignin before depolymerization; (b) and (d) are pine lignin after depolymerization.

Conclusion

We developed a one-step, CeCl3-based photocatalytic strategy to not only achieve highly selective Cα–Cβ bond cleavage but also produce functionalized aromatics, such as aldehyde (up to 97%) and N-containing products (up to 95%) in high to excellent yield from both β-1 and a wide range of β-O-4 lignin model compounds at RT. The long-life catalytic performance of this CeCl3 catalytic system was verified by catalyst reuse experiment, as well as on/off switching experiments. More importantly, this method could be utilized for the photocatalytic depolymerization of both trimeric lignin model compound and natural lignin product, thus providing a convenient and economic-viable way to access highly value-added platform chemicals through lignin depolymerization.

Scheme 6 | Photocatalytic depolymerization of natural pine lignin.

Supporting Information

Supporting Information is available.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 21975102, 21871107, and 21774042).